The Disconnect Between Tech Advertising and User Expectation: A Case Study in Dive Watches

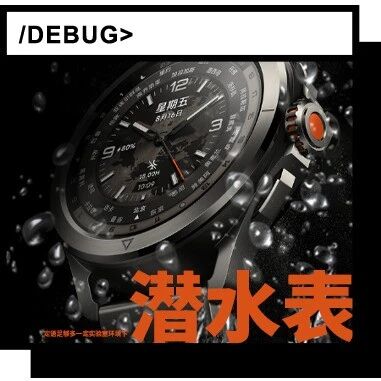

As AI systems move beyond text, the broader technology sector continues to grapple with a fundamental challenge: the gap between advertised product capabilities and real-world user experience. This issue was recently highlighted by an incident involving a Xiaomi dive watch, which brought into focus the often-complex relationship between technical specifications, marketing claims, and consumer understanding.

Highlights

The incident began when a user reported water ingress in their Xiaomi dive watch after four days of diving. Initially, Xiaomi's after-sales service attributed the issue to "human factors," denying a refund or repair. After further communication, a free repair was offered, but with the caveat that the watch was "not recommended for going into the water again."

This situation gained wider attention online, with some content creators misrepresenting Xiaomi's general water resistance disclaimers for non-dive-certified watches as applying to the dive-certified model. This led to public frustration, with many questioning the practical utility of a "dive watch" that seemingly could not be used for diving. Xiaomi subsequently issued a clarification, and the immediate controversy subsided.

Context

The core of the issue, however, extends beyond this specific event. It underscores a broader "cognitive misalignment" prevalent in the tech industry. Manufacturers often rely on certifications and laboratory-tested parameters, while consumers interpret product descriptions based on practical, real-world usage scenarios.

Xiaomi's dive watch, for instance, passed the SGS EN13319 international diving certification and was advertised to support various diving modes, including recreational scuba diving, freediving, and instrument diving, up to a depth of 40 meters. For many consumers, this implies direct usability for diving within these parameters.

Technical

From a structural standpoint, the EN13319 certification signifies a product's waterproof performance under specific laboratory conditions. The 40-meter depth rating indicates resistance to static pressure in a controlled environment, not necessarily dynamic conditions encountered in open water. The real ocean presents variables such as currents, salinity, temperature fluctuations, and impacts, which can significantly alter a device's performance compared to lab results.

Moreover, more stringent professional dive watch certifications, such as ISO 6425, exist, which incorporate more detailed requirements for actual use scenarios. However, even these higher standards cannot fully simulate all real-world uncertainties. Waterproof performance is also not permanent; seals degrade over time, and physical impacts can compromise integrity. Many manufacturers include disclaimers stating that "water resistance is not permanently effective" and that "water ingress is not covered by warranty."

By comparison, other brands like Huawei with its Watch Ultimate, also advertise 100-meter diving support based on the EN 13319 standard. Even specialized brands like Garmin, with its Descent series designed for diving, utilize the same underlying EN 13319 certification. This suggests a common industry practice where certifications serve as a threshold but do not guarantee immunity from real-world failures.

What Comes Next

This "cognitive misalignment" is not unique to dive watches. Similar patterns are observed across various tech products. Smartwatches, for example, are often marketed as "wrist hospitals" with features like heart rate, blood oxygen, sleep quality, and stress monitoring. However, the practical utility and accuracy of these features, particularly for medical purposes, can be limited. For instance, stress levels are often derived from heart rate variability, which provides a narrow view of a multi-dimensional physiological state.

Meanwhile, TWS earphones frequently highlight "maximum noise reduction depth" (e.g., 40dB or 50dB) as a key selling point. In practice, this maximum reduction often applies only to specific low-frequency noises, with performance significantly diminishing for mid-to-high frequency sounds like human voices.

Even mobile phones, for years, have emphasized pixel count as a primary indicator of camera quality. However, photo quality is equally dependent on lens optics, sensor size, and algorithmic optimization, often leading to flagship phones with lower pixel counts outperforming mid-range devices with higher megapixel specifications.

This recurring pattern suggests that manufacturers often highlight impressive parameters and certifications prominently, while crucial preconditions and limitations are relegated to fine print. This practice contributes to a growing rift, where manufacturers feel they have fulfilled their obligations through disclosures, and consumers feel misled by what they perceive as exaggerated claims.

Looking ahead, the resolution of this phenomenon may depend on market dynamics. Either manufacturers will face significant setbacks due to the discrepancy between advertising and actual experience, or the industry as a whole will gradually adopt a more transparent and responsible advertising consensus driven by user feedback and market pressures.